By Leo Adam Biga

Author-Journalist-Blogger

Originally appeared in the Omaha “Jewish Press” in 2005

That’s as close to an explanation as Lola Reinglas can offer in making sense of her Holocaust survival. An Omaha resident since 1949, Reinglas and her sister, Helena Tichauer, survived a series of internments, some together-some apart, that defied reason except for the intervention of fate and their own indefatigable will.

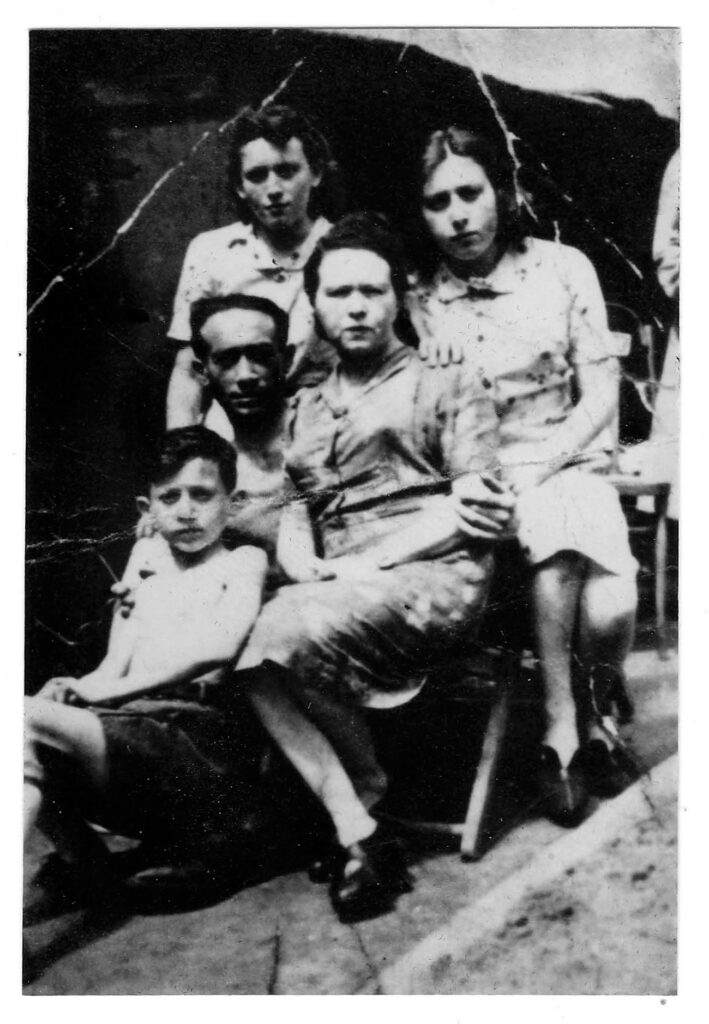

“We’re both very strong women,” Reinglas said of she and her sister. Born Lola and Helena Schulkind, they were the well-to-do daughters of a proud, old Krakow family that included a younger brother, Nathan. Their father Karol was an electrical engineer and their mother Karolina a model of refinement.

“We’re both very strong women,” Reinglas said of she and her sister. Born Lola and Helena Schulkind, they were the well-to-do daughters of a proud, old Krakow family that included a younger brother, Nathan. Their father Karol was an electrical engineer and their mother Karolina a model of refinement.

Like so many Shoah families, the Schulkinds remained intact but a short time in the war. First, Nathan was taken away. He soon perished. Then, a grandmother was killed. Finally, Lola was sent to one camp while Helena and her parents remained at another. Except for a short separation, Helena and her mother remained together during the entire ordeal. Their father survived mere days after being liberated.

After the Holocaust, Lola could not find her sister and mother. By the time she did, they were headed from Sweden to South America. Lola met and married fine cabinet maker and fellow survivor Irving Reinglas in a refugee camp and they emigrated to America with their first child. The couple’s new life here saw them build a business and raise a family. Meanwhile, Lola’s sister and mother built a new life of their own — in Uruguay, where Helena met and married Walter Tichauer, a German Jew who fled there after Kristallnacht. Lola was finally reunited with her mom, in 1957, when Karolina visited the States. Three more years passed before she saw Helena. On a 1961 visit to Uruguay. Lola laid the groundwork for her mother, sister and sister’s family to move to America, which they did in 1963.

Each sister’s odyssey is a compelling lesson in human intolerance and endurance. Helena’s story will be chronicled in an upcoming Press edition. This is Lola’s story.

By the time the former Lola Schulkind reached Plaszow, the forced labor camp turned concentration camp outside Krakow, Poland depicted in Steven Spielberg’s film Schindler’s List, the words of her father reverberated in her head.

“He always told us, ‘Remember one thing — live. No matter what, try to do your best and live. Don’t give up.’ And whenever it was very bad, somehow I heard the voice of my father. Even to this day,” she said, “when things go bad…I hear that voice, ‘Don’t give up.’ I don’t.”

It was at Plaszow she believes Oskar Schindler saved her life. The camp was where the Jewish workers under the German industrialist’s protection were interned for a time. Schindler, she said, was a well-known figure in the camp, but his good works on behalf of Jews were not. His enamelworks factory was nearby. He operated a pot and pan factory inside the camp and was often in and out of Plaszow, where, it turned out, he bribed the commandant to keep “his Jews” safe.

One night, a teenaged Lola was caught past curfew sneaking food to her father in the men’s barracks. What happened next was something she didn’t understand until years later — long after Schindler’s rescue efforts were revealed. Taken to a hill by uniformed men, a man in the group she now recognizes as Schindler “took a gun and put it to my head,” she said. “I thought he was going to kill me. But he started hitting me…beating me, beating me…until I lost my consciousness.” She now surmises that with German soldiers looking on, he could not let her go with only a warning and, “instead of killing me, he beat me” and, thus, “saved my life.”

Plaszow was a Dante’s Inferno overseen by sadistic Amon Goeth, a large man often seen on horseback or surrounded by dogs trained to attack “on his command of Uda. When you saw him, you knew trouble was coming,” Lola said. Built over a Jewish cemetery, inscriptions on desecrated tombstones could be read in the pavement covering the heavily fortified camp’s roads. Random, public executions orchestrated by Goeth and his SS staff were done for sport and intimidation.

It was there Lola and her family arrived in 1942. The previous several months the family had been confined, with thousands of others, to a barbed wire and stone wall enclosed ghetto in the Podgorze district of Krakow. Even after generations of living in Poland, the Schulkinds and their fellow Jews were systematically made enemies of the state by edicts of the German occupation that began in 1939. “We were born and lived there from one generation to another for probably 100 years, but we still had no home. It was like we never belonged,” Lola said.

Almost immediately, Jews lost their rights, their jobs, their possessions. Curfews limited their movements. Yellow Stars of David identified them. They were targets of roundups, beatings, killings. With her own eyes, Lola saw male Orthodox Jews accosted on the street by thugs and the victims’ beards savagely “cut off, skin and all,” with knives. She knew of people arrested and never being seen again.

Lola, who’d completed elementary school and one year of business school, was 14 when the war broke out. The Shoah not only ended her early formal schooling, but her childhood as well. Her father had to give up a business employing several people. When ordered to leave their homes in March 1941, Jews were marched to the ghetto prepared for them, where they lived in squalor. Allowed to take only five pounds of articles per person, they brought whatever clothes they had.

Jews were moved into what had been the homes of Gentiles, who, in turn, left to take over the Jews’ abandoned homes across the river.

The Schulkinds occupied a two-room flat with another family of five in an overcrowded apartment house. There was Lola and Helena — two years her senior— then-11-year-old Nathan, and their parents. “We thought it was bad before we went to the ghetto. Then, we went to the ghetto. Not enough food. Ten to fifteen people in two rooms. We slept on the floor. No privacy. No way to take a bath. The living conditions were terrible. We thought, This is the worst. Well, how wrong we were,” said Lola. Nothing could prepare them for what lay ahead.

Ghetto life was a particular shock to the Schulkinds, who’d enjoyed a privileged life replete with servants, summer-long stays in cottages, winter skiing vacations at lodges, et cetera. A bookworm, Lola had no access to her beloved literature.

The historical anti-Semitism harbored by a large segment of the native Gentile population, combined with the Nazis single-minded implementation of the Final Solution, left few friends Jews could turn to for aid. What help did exist, in the form of food or shelter, exacted an exorbitant price and extraordinary risk.

Lola’s father, whose plan to take his family to Russia years earlier was rejected by her mother, boldly refused handing over his valuables to the authorities. “He took a great chance,” she said. The family used jewelry and silver to barter with Poles and Germans for precious food provisions in scarce supply..

The ghetto was a despairing place where time stood still. Nothing beyond the imposing stone wall or the forbidding armed guards surrounding it existed. “We were afraid because we never knew what was going to happen tomorrow,” said Lola, “or for that matter in an hour from now.” People disappeared. Others got shot. When word came the Germans were liquidating the ghetto, she saw soldiers throw infants out of third-floor windows.

Making the harsh life there a little more bearable was her father’s eternal optimism. Despite having come back from service in the Austrian Army in World War I a man who “didn’t believe in anything” having to do with God, she said he was an inspiring fellow who buoyed people’s spirits. “When you’re an optimist like my father was, you always believe that better days are coming. He was always telling people. ‘Tomorrow is going to be better.’ He always believed.”

Hardly a pacifist, he wanted more than anything to see justice done to his people’s tormentors. “My father always said, ‘No matter what’s going to happen, I’m going to stay alive and see the Germans beaten, but good.’ And, believe it or not, he survived the concentration camp and lived to see himself liberated and the Germans beaten like dogs. Two days later, he died.”

There was no leaving the ghetto unless chosen for a work detail at a forced labor project outside it or you were brazen enough to sneak out. Lola was picked to work as a cleaning girl at a Krakow hospital where wounded Germans were treated. Mornings, she was part of a group of slave laborers taken by truck to their assigned jobs. The manual labor was new to her. “It was the first time in my life I scrubbed floors, cleaned windows, cleaned toilets and washed dishes,” she said.

Demeaning as the work might have been, she counted herself lucky as it meant access to extra food. “Whatever I could save, I brought it back to the ghetto for my parents and my sister and brother to eat.” She said to her surprise some Germans at the hospital were “very good” to her. “If they had food they couldn’t eat, they’d tell me, ‘You take it.’ I was very happy I could bring some food.”

As her saga unfolded, Lola found working “the only thing that would save you…No matter where you were, as long as you could work, you were OK. Once you just laid down…then they took you and shot you like a dog. A lot of people physically and mentally couldn’t do it. They gave up. They said, ‘What for?’ And they died.”

Death was never far away. Not long before the ghetto’s liquidation, she recalls orders being given via loudspeaker for all inhabitants “to concentrate in one place.” They were told to bring only what they could carry, which meant something awful was coming down. Sure enough, she and her family watched in horror as an estimated 1,500 men, women and children were ordered out of the crowd — to stand in front — where they were killed by machine gun fire. “I witnessed that. You know, I had never seen my father cry before. He was crying like a baby and blood was running like a river. It was horrible.”

The ghetto dwellers were assembled once more, prepared to march to an unknown destination, when her brother Nathan was pulled out of line by the Gestapo. “The man said to him, ‘You can’t go.’ He was 13, but very skinny and very little, and they were pulling out all the old people and young children and the ones whose looks they didn’t like.” That’s when her mother bolted for her only son. “She grabbed him and went back in line with him. The man came and looked at my mother and he said, ‘If you’re going to do that, I’m going to kill your son and you right now. He can’t go.’ So, they put Nathan out and put him on a truck to Auschwitz. That was the last time we saw him. They brought him straight to the ovens.”

The remaining human caravan from the Krakow Ghetto ended up in Plaszow, a compound around which an electrified fence ran. Stripped naked, prisoners endured another selection process that eliminated the weak and old. It was then and there that Lola’s paternal grandmother was forced to dig her own grave. “She said to us, ‘If that’s what God wants, that’s what’s going to be.’ She went in that grave with her bible, and they shot her right in front of us,” Lola said.

Brutality became a numbing reality at Plaszow. Random acts of barbarism the order of the day. Once, Lola was forced to watch the hanging of a man caught trying to escape. “And so help me God I could hear the bones crack in his neck. They let him hang three days, so everybody that worked saw him. I said, ‘No, this is it, I will never survive.’” She did survive, but only by steeling herself. “I was like a stone. I left everything behind me. I had no feelings.” When the woman next to her in the barracks died overnight, Lola waited until the morning to report it so that she could consume the extra ration of bread and coffee. In such a place, she said, “We could not speak about the future — only about what was.”

Upon first arriving at Plaszow, Lola continued her routine of being brought to thehospital to clean. Later, she worked in a quarry breaking stones with a hammer to make gravel. Once, she switched jobs with her ailing mother, who was too weak to carry a yoke laden with buckets of water. Lola briefly worked in a paper factory. Then, one day the factory was closed and she and others loaded onto cattle cars and taken by train to the first of two nearby camps whose German munitions factories she worked in. It was 1944. Her remaining family stayed behind at Plaszow.

At Skarzysko Kamienna, Lola operated a machine making anti-aircraft shells. “You had a quota to make 80,000 shells per shift,” she said. “If you couldn’t make your quota in eight hours, you worked until you did. Sometimes, you worked 12-14 hours on one slice of bread and a cup of coffee.” Unable to meet the quota any other way, workers mixed defective shells in with the good ones. Once, a woman foreman discovered a bad shell in Lola’s batch and used a riding crop to administer “25 lashes on my rear end,” Lola said. “I couldn’t sit for six months.”

In 1945, Lola went to Czestochowa, the site of another munitions factory. There, she fell ill. “I could not eat. I could not drink. I was down to 60 pounds.” Later, she found herself again in transit by train — this time to Germany — when the train stopped at night. By morning, the captives discovered their captors were no where to be seen. The advancing American Army had set the Germans on the run and the emaciated refugees were soon rescued. The war was over. “I was free,” Lola said.

After months of rest and nourishment in an American-run refugee center, she felt strong enough to travel. “I didn’t have money. I smuggled myself on a train to Poland. It took me three weeks to get to Krakow.” She went to her family’s home, praying for some sign of her family, only to find strangers. “The woman there said to me, ‘Oh my God, you’re still alive?’ I said to her, ‘You drop dead.’” Undeterred, she found an uncle who’d survived and stayed with him. Two cousins joined them. In Krakow, she learned the fates of her brother and father. Awaiting word on her mother and sister, they located each other and began corresponding.

Just when it seemed the danger was ended, pogroms broke out in several Polish cities. “Poles started shooting Jews in the street. They didn’t want us. My uncle said, ‘This is no place to stay.’” Lola said. Like hundreds of thousands of other survivors, they wanted out of Europe. Ironically, they fled first to occupied Germany, where displaced persons camps were a way station out. Lola, her uncle and cousins went by way of Czechoslovakia, where they stayed a week and were treated royally. “The people were wonderful.” In Germany, they lived in the Foehrenwald refugee camp, where she fell in love with Irving Reinglas at first sight. Married in ‘46, they lived in Munich until ‘49, when they came to America under the auspices of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), a major supporter of Jewish survivors in DP camps.

The ship carrying Lola and Irving docked in New York Harbor on Thanksgiving Day. Given the choice of staying in New York or relocating, they opted instead for a smaller, slower city. HIAS officials suggested Omaha, where the couple knew not a soul. With Jewish Community Center sponsorship, they settled here and cobbled together a successful life. They learned English. They ran their own business, Easy Chair of Council Bluffs. They gave their two daughters, Jeanatte and Ann, a good education and every advantage. Lola eventually regained her sister and mother.

The ship carrying Lola and Irving docked in New York Harbor on Thanksgiving Day. Given the choice of staying in New York or relocating, they opted instead for a smaller, slower city. HIAS officials suggested Omaha, where the couple knew not a soul. With Jewish Community Center sponsorship, they settled here and cobbled together a successful life. They learned English. They ran their own business, Easy Chair of Council Bluffs. They gave their two daughters, Jeanatte and Ann, a good education and every advantage. Lola eventually regained her sister and mother.

Today, Lola is without her Irving, who died in 1988. The grandmother of two stays active. A longtime volunteer at the Rose Blumkin Home, she now gives her time to the Methodist Hospital gift shop. Except for an occasional speaking appearance or interview, she doesn’t revisit the Holocaust. “I don’t live in the past. It’s not that I have forgotten. I know I’ve been to hell and back,” she said, “but this is not my main subject. I think about today and tonight. If I lived in the past, I would have been in the nut house a long time ago.”

The Holocaust, she said, is an unfathomable episode whose echoes, sadly, reverberate in latter-day oppression and violence. “There is not a word in the dictionary that describes the atrocities. And for what? Wherever you look today, people are fighting. And for what? For power. For nothing else.”