By Leo Adam Biga

Author-Journalist-Blogger

Originally appeared in the Omaha “Jewish Press” in 2000

For the first 52 years of his life Fred Kader lived everyday in the shadow of a lost past. An orphaned child of the Holocaust, Kader’s early years remained an unfathomable mystery that he hoped one day to solve so that he might finally come to know how he survived the Shoah as a small boy in his native Belgium.

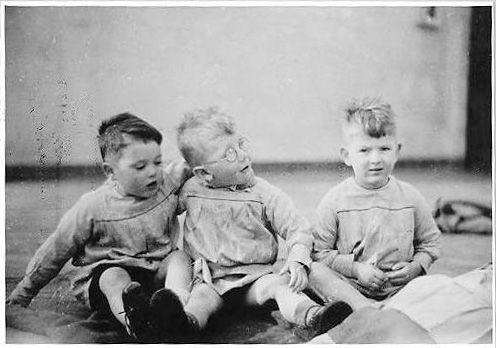

That he had been one of an estimated 4,500 hidden children in his homeland during World War II he already knew. That he was the lone surviving member of his immediate family he was certain. That he ended up in an orphanage reserved for Jewish children he definitely recalled. That an uncle found him after the war and took him in to live with his family he also remembered. But precisely how he came to be hidden, where he was protected and by whom were details frustratingly outside his memory’s reach. After all, when the events that eventually, tragically separated Kader from his family first transpired he was about 4 years old — an age when distinct memories are rare in even the best of circumstances. Given the trauma he endured during the four years he was in hiding, he no doubt buried memories that he might otherwise have retained. Adding to his dilemma was the sad fact that the few members of his extended family who were left could provide only partial answers to the questions that dogged him all these years later.

For Kader, a pediatric neurologist with his own private practice in Omaha, the strain of not knowing his own life history left an ever-present void he could not fill and with the disturbing sense that pieces of this puzzling odyssey lay just beyond his grasp. Kader, a soft-spoken man with sensitive eyes, described what it is like to be burdened with such a gulf inside.

“It’s like a big box of unknown,” he said in his delicately-accented voice. “It’s a big box that’s empty, yet it isn’t empty. You know it’s full of things but there’s no way of getting into it. When you have a chance to talk about it, you remember so little that it takes just a few minutes to put in words what you can say about it because the rest of you just represses it all. The pieces you know fill just a small corner of the box and the rest of the box is empty and yet you know it isn’t. And you know whatever is in there certainly affected you and influenced you and has a direct relationship to who you are and what you do. It’s a strange kind of void. It’s part of you and yet it’s separate from you. You must keep going in spite of it and just try and accept it.”

Fragments and snatches of memories from war-torn Europe haunted him, but he could never make sense of them or be sure they were not fabrications of his imagination. Besides, the images in his head were obscured — like shadows filtered through a screen. For example, he recalled resting his head in someone’s lap and crying during a noisy, nighttime road trip, but could not remember who consoled him or why or where he was traveling. Then there was the image of him wandering the streets as a little boy lost and somehow being whisked away to safety by someone. Why he was alone and who rescued him he did not know.

“It was all bits and pieces. Some of it I knew was facts, some of may have come from something I remembered and other parts of it may have come from something I read and incorporated. After a while, things kind of merge and run together and it’s hard to tell what is factual, what’s a memory and what’s a nightmare.”

Striking an uneasy truce with his seemingly irretrievable and intractable past, Kader got to the point of never expecting to fully know what caused him to be spared amid the Holocaust. Then, at the urging of a fellow hidden child from Belgium who, amazingly enough, had also wound up as a pediatric specialist practicing in Omaha— child psychiatrist Tom Jaeger — Kader joined his friend at the First International Gathering of Children Hidden During World War II in a shared search for clues to their missing stories. Heading into the 1991 conference in New York City, the then-52-year-old Kader adopted a decidedly guarded attitude about what he might find, so as not to be disappointed if his questions turned up no real answers. “Emotionally, I was trying to stay pretty calm, cool and collected because I didn’t want to build up any kind of false hopes of being able to find something out,” he said. “I mean, who was going to know anything about this one little Jewish boy in the middle of this immense devastation that went on in Europe?”

Much to his astonishment, however, he discovered a wealth of information that, for the first time, gave him a near complete picture of how his own hidden child story played out and revealed the identities of those individuals whose actions shielded him from almost certain death. These revelations came about as the result of Kader meeting people at the conference who knew his story either as researchers or as first-hand participants who aided his survival.

First, he met writer Sylvain Brachfeld, the author of a book chronicling the hidden children of Europe, including those in Belgium, and who upon hearing Kader’s original name — Jeruzalski — immediately placed him and his story. “It was really meeting Brachfeld that just sort of put the key in the lock and unlocked the door,” Kader said. “I mean, he just pinned me. He said, ‘I know who you are and I know exactly what page you’re on in my book. I know exactly what you looked like as a kid.’ And the door just swung open and from there I met all these people who knew me and knew what had happened to me. I didn’t know them, but they recognized me. They were actually able to corroborate some of the things I had in my memory. They dated it, they placed it, and a timeline started, so to speak, and my early years sort of got sorted out. It was like catching up with my life story. It was overwhelming.”

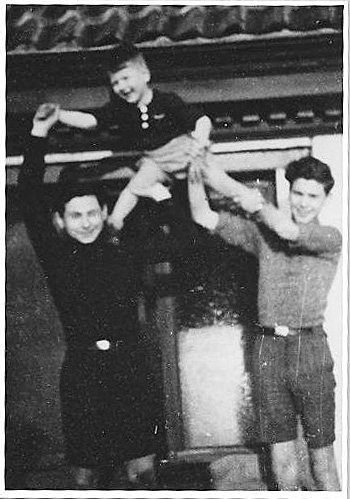

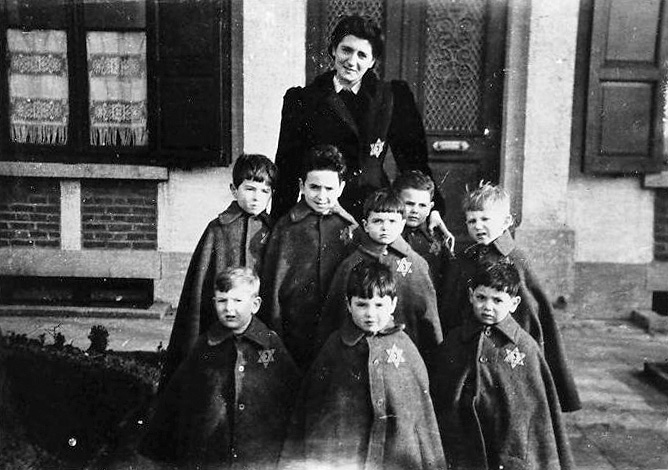

Perhaps the most powerful corroboration came from Marcel Chojnacki, who informed Kader that it was his lap the then-4 year-old Kader rested on during that mysterious and road trip at night. It turned out Chojnacki actually discovered Kader and some other orphaned children waiting to be transported to Auschwitz. He put them in the hands of a rescuer, Madam Marie Albert Blum, a nurse who arranged for the waifs to be transported by truck back to safekeeping. At the time, Chojnacki was a fellow hidden child, although older than Kader, in the charge of Blum, who operated the Home of Wezembeek, a former sanatorium-turned shelter for Jewish children that was part of an underground network of safe houses throughout Belgium. The child-saving network that Blum participated in was known and somewhat tolerated by the Nazis and was sanctioned and partially protected by high levels of the Belgium ruling class, including Queen Elizabeth of Belgium.

Before Marcel Chojnacki and Madam Blum intervened on his behalf, Kader had already been rescued twice. His story of loss and survival began in September, 1942. The mass deportation of Jews in Belgium was already well under way. His father had been rounded up with other Jewish men and sent to a forced labor camp in France. His older brothers were already on their way to death camps. One day, Kader found himself with his mother at the Antwerp rail station, where trains were transporting Jews to various way stations en route to Auschwitz. A surviving aunt, who was also at the station that day, later told him that his mother made the heart wrenching decision to try and save her lone remaining son by ordering him to walk away from her. His mother knew he stood a chance because of his Aryan-like features — namely, blond hair and blue eyes. Like a good little boy, Kader obeyed his mother and wandered away, never to see her again. He does not remember his mother’s face or voice or smell or manner. No photographs of her or any member of his family exist. Of that fateful day, he recalls only aimlessly walking the streets of Antwerp and being swept up and carried away by some unknown good angel.

In recent years Kader has learned his rescuer that day was a nun who escorted him to a house near Antwerp set-up for hiding Jewish children. Called the Home of the Good Angels, Kader was there with five other children only a short while before the house was raided. Kader and the other children were sent to Malines, a major train terminal and deportation site for Auschwitz. Meanwhile, the Wezembeek orphanage was also shut down by the Nazis, who forced Madam Blum and the dozens of children in her protection to move to Malines. It was in Malines where the paths of Kader, Blum and Chojnacki intersected. After being thrown out of their hiding place, Kader and his fellow young vagabonds, suffering from lack of food and sleep, were holed up in one corner of a former army barracks in Malines. Soon, Blum and her caravan of orphans arrived, too — unaware of the presence of Kader’s group. All of the children were slated for transport to Auschwitz. A convoy of trains carrying Jews from France were to be their passage. Civilian trains were being employed at this time in the transport of Jews. That day, the trains were late arriving, Kader has learned, because some captives kept jumping off, causing repeated delays as the guards recaptured the fleeing prisoners or shot them on sight. In an ironic and tragic twist, it turns out Kader’s father and uncle were on one of the trains en route to Malines. Neither Kader nor his father could have known the other was so near. And, as fate would have it, Kader’s uncle — his father’s brother — escaped into the countryside during one of the train convoy’s unscheduled stops, but his father did not.

During the better part of a day and night, the enterprising Blum took advantage of the delayed trains to negotiate with German army officials, some of whom could be bought with bribes, for the release of the children to her care and for a guarantee of their safe transit back to Wezembeek. As the day drew on, some of the older children with Blum, including Chojnacki, wandered off to investigate the barracks compound around Malines. And it was while nosing around one barracks that Chojnacki and his mates came upon the huddled, ragtag forms of Kader and the others, who were brought to Blum’s attention and added to her protective custody. Malines proved to be a crossroads of hearts and fates. While Kader, his uncle, Madam Blum and her wards were spared the horror of Auschwitz, the brutally efficient Gestapo were so intent on meeting their deportation quota that they dragged patients out of hospitals and onto the trains to take the place of the children. It is presumed Kader’s father went to his death in Auschwitz too.

When, in 1991, Kader met up again with Marcel Chojnacki and learned how he came to be with him under Blum’s protection, it was like coming face to face with his long “lost brother” and finding the once closed door to his unknown past opened wide. Kader said, “He knew how I came to be saved. How I survived. Meeting Marcel, the door didn’t just swing open, it came off the hinges. It was just a flood of information. It couldn’t come fast enough. It grew exponentially. I was trying to keep my feet on the ground to make sense of all this.” He and Chojnacki have become close friends in the ensuing years. As part of his attempt to reclaim his past, Kader has traveled to Belgium to visit many of the sites he spent his hidden childhood in and to thank Chojnacki, Blum and other individuals who played a role in his survival. For Kader, the term hero only begins to describe how he feels about Blum, a Jewish woman who risked her life over and over to aid helpless children like himself. Blum has been recognized in her own country and around the world for her rescue efforts.

Kader’s immediate post-war life, like that of many hidden children, was an unsettled affair. He stayed at a convent for a time and for two years he and other children fended for themselves at the by-then vacated Wezembeek facility and grounds. He developed street smarts during this time. “You had to mature fast if you were going to survive,” he said. His uncle found him — purely by accident — and brought him to live with his family. Kader said his uncle rarely spoke about the war or the personal losses endured. “It was too painful to talk about it. He survived and my father didn’t. He was the sole survivor of the family. And here I was reminding him of the family that he lost.” He said his uncle’s family treated him well, but his orphan’s sense of abandonment and wariness made him resist their kindness. “As a kid, you realize there’s nobody there for you. You’re it. You’re on your own. You don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow. Whether you’re safe or not. You lived through the war. You ended up in an orphanage. Then, you’re at your uncle’s place. They tried very hard to make a family life for me, but I don’t think I let them because everywhere you go, you wonder, How long am I going to be here?” Kader’s mistrust and alienation only intensified when, at age 11, he was sent to live with a great aunt and her family in Montreal, Canada. “And then all of a sudden you’re transported to a different place. To a different country. With a different family. So, again, you’re left wondering How long” How come? and What’s going to happen next? I looked at it as the next step in being alone and traveling on an ongoing basis. It took me years and years to make sense of my existence.”

Finally, with time, he came to feel he did have a home and a family, after all. “It took a while to accept that there was no more wondering about whether I belonged somewhere. As you get a little older you stop wondering what’s going to happen and you realize this is not just another temporary stopping place, but that this is it. This is the end of the line. This is where you’re going to become part of a new family and this is where you’re going to plant roots.”

Gradually, Kader began to flourish in his new life. He did well in school, especially upon discovering that education was an opportunity to make something of himself and, in a way, to make up for some of what he had lost. From the time he arrived in Montreal he felt compelled to serve others. “I knew I wanted to do something to help people.” He couldn’t fully understand it then but he has since come to believe his wartime experiences are what drove him to be a physician focusing on children. “It’s no accident I found myself working in medicine with kids. My past was a means to an end. Obviously, knowing what happened to me the first seven years of my life does give you a basis to realize how you got to this point and how you got be who you are. It makes you more whole when you can understand what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.”

After training in Canada and the United States, Kader settled in Omaha in 1974, where he worked at the University of Nebraska Medical Center before entering private practice. He and his wife of 36 years, Sarah, are parents to three grown children (two of whom are professionals working with children) and are grandparents to three.

Since discovering his past, Kader, now 62, has spoken publicly about his experience as well as about the horrors and the lessons of the Holocaust. He feels it is the obligation of all survivors to do so. “We have to tell our story because it’s the only way we can teach people what happened. You hope people will listen

and you hope people will learn. If you know about it, then when you see bigotry in front of your eyes you’ll recognize it and then maybe you’ll try to put a stop to it.”

Meanwhile, Kader’s search for more details about his family’s exact fate may never fully be completed. For example, his investigations have not been able to determine what happened to his only sister. “There’s still little pieces missing,” he said. “Things that I’ll probably never know. You never quite get to the end. So there’s still a sense of not totally putting closure to it.”