By Leo Adam Biga

Author-Journalist-Blogger

Originally appeared in the The Reader in 2005

The apt words belong to Lincoln, Neb. resident Lou Leviticus, a square-headed terrier of a man who as a youth in his native Holland survived the Holocaust partly due to his talents as an artful dodger. He escaped the Nazis more than once, even when those closest to him were caught and put to death. As an orphan on the run he became one of scores of hidden children in The Netherlands, his survival dependent on a cadre of strangers that cared for him as one of their own.

Today, when telling his saga to young Hebrew students at Temple Israel Synagogue in Omaha, the spoken truth sounds less like glib bravado than a solemn proverb. And, like an answered prayer, members of the Dutch underground rescued him. He regards those that helped him, especially Karel and Rita Brouwer, as his “heroes” and “protectors.” During his time in hiding Lou endured and did some unspeakable things. An archly unsentimental sort, he sheds no tears over what happened. Despite it all, he emerged a life-affirming dynamo. The retired University of Nebraska-Lincoln agricultural engineering professor first came to America in the mid-1950s to obtain his Ph.D. He married, raised a family, got divorced. He wed his present wife, Rose, a native of Great Britain, in 1982. He became a U.S. citizen four years ago. Today, he is an agricultural engineering consultant.

Until quite recently he kept his story to himself. That changed when the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation requested he tell it for the sake of posterity. The Los Angeles-based Foundation, which filmmaker Steven Spielberg formed after completing Schindler’s List, is dedicated to recording and preserving the largest repository of Holocaust survivor stories in the world. Beginning in 1995 the organization, conducted videotaped interviews with survivors from every corner of the globe. Some 50,000 interviews have been cataloged for use by scholars.

In 1996 Lou shared his story with Omahan Ben Nachman, a Holocaust researcher and Shoah-trained interviewer who’s collected dozens of testimonies. Since then, Lou has written his memoirs and related his tale to youths at schools and synagogues. Why, after all this time, is he bearing witness now?

“The only reason I do it,” Lou said, “is to maybe make somebody think about it and realize how fortunate they are. That they should not take their lives so easily for granted. That they have a little more gratitude for what they have…because what happened then can happen again. It is happening again. Look at Chechnya. Look at Kosovo. Look at the skinheads in this country. There is hatred. People are cruel. And I do now feel it as an obligation, not necessarily to this generation, but to my school buddies, my parents, my grandmother, and to all those people. If I don’t tell their story, what else is left of them except their names in a register?”

In a recent interview, he recalled those dark years. Speaking from the deck of his comfortable tree-shaded home in Lincoln, the scene could not have been more incongruous with what he described. Despite what eventually transpired, his homeland was a tranquil place before the invasion. Pre-war Holland, after all, was a civilized society. Its large Jewish population enjoyed complete freedom, if not full acceptance. Lou and his parents led a privileged life in Amsterdam. As foreign correspondent for a large recycling company, his father, Max, handled relations with foreign clients. An outdoorsman, Max enjoyed long bicycle rides and walks in the countryside. Lou’s mother, Sera, was a socialite and spiritualist who gave bridge parties and hosted seances at the family’s large home.

As a boy he often joined his mother at Heck’s Cafe, a swank gathering spot for the smart set, where he listened to live band music while she hobnobbed with friends.

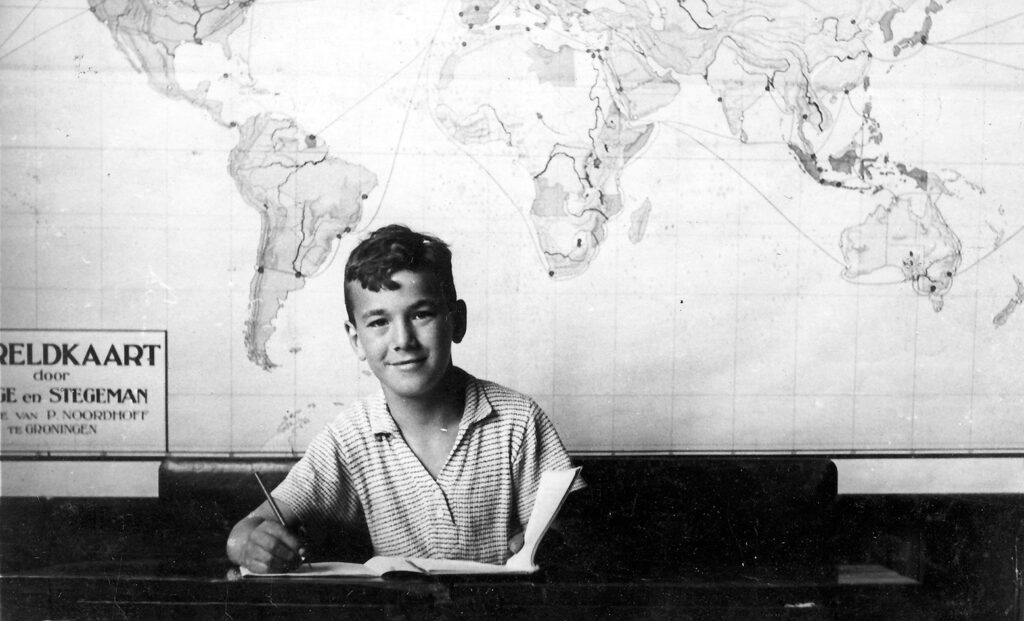

Music, especially opera, held young Lou enthralled. He had his own radio and spent endless hours listening to favorite tenors and to detective programs. An avid reader, he fancied the adventure tales of German author Karl May. Despite being undersized, he was athletically adept and belonged to swimming and soccer clubs. A cinema lover, he skipped Hebrew school to catch the latest movies.

His family lived quite close to Anne Frank’s family. A cousin of hers, Paul Frank, was a friend and playmate of Lou’s. Because she was two years older than Lou, he only knew her casually, but recalls her as a “nice girl. She was more mature than me.”

Admittedly “a spoiled brat” doted on by his paternal grandmother, Lou lived a carefree life. His parents, who employed a servant, had their every need met. The family’s idyll ended May 10, 1940 when Germany invaded Holland. The Dutch, who remained neutral during World War I, had felt protected from the brewing storm in Europe despite Germany’s increasingly ugly rhetoric and military incursions. Caught unprepared, Holland’s meager defenses were quickly overwhelmed by the blitzkrieg. The Netherlandscapitulated five days after the attack began. Even though he was not quite 9-years-old, he recalls it all. “I remember all five days. For us kids it was the greatest adventure in the world. We didn’t see the sickness. We heard people were being killed, but we didn’t see it. We did see German planes in the air and men shooting at them. It was exciting.”

Perhaps his most vivid memory is the sight of a city under siege at night, its lights darkened and streets emptied owing to the mandated curfew and blackout. The horror was finally brought home when he found his father, a WWI vet, returned home from serving in the civil defense corps and sobbing over Holland’s surrender. “I can still see him sitting in the side room crying. It was the first time I saw my dad cry. I remember asking him, ‘What’s the matter?’ But he couldn’t talk.”

Lou, who’s researched events leading up to the German conquest and the ensuing terror campaign, said much of the Dutch ruling class held pro-Nazi sympathies and as such these Fifth Columnists aided Germany in subduing The Netherlands. Beyond politics or prejudice, he said, the compliant nature of the Dutch people, combined with a meticulous citizen registration system, made it easier for the Nazi regime to exert its will there.

“My feeling is that the Dutch have always been very obedient to authority — any authority. The Germans had the authority and when they installed a Dutch puppet government, that was the government, and therefore they were obeyed. The Dutch also had a population registration system in place unparalleled in its accuracy in Europe. That system should have been destroyed when the Germans occupied The Netherlands, but the people who ran it were so proud of their work and so pro-Nazi they handed it over in full to the Germans, who used it to curtail the activities of Jews and other undesirables.”He added the Germans were “very cunning” in passing decrees that cut-off Jews from the general populace. “It started with very little things. They never targeted the whole population — otherwise, that would have probably created unrest — but targeted sections, making each segment register and abide by restrictive laws. Each week there was a different order affecting some group, and the others said, ‘Well, it’s only them,’ and in the end it was everybody. The noose was tightening, but most people didn’t realize it, and by the time they did it was too late.”

The first anti-Jewish regulation affecting him was a 1941 law banning Jews from all movie theaters except the single Jewish-owned cinema in Amsterdam. “Soon, it became impossible to go there too because there were always Nazi youths waiting outside to cause mischief. Even if you were with grown-ups it sometimes got a little bit hairy.” He next felt the sting of anti-Semitism when forbidden from entering parks and from holding membership in sports clubs. At the same time, the Nazi propaganda machine worked overtime inflaming anti-Semitic fervor.

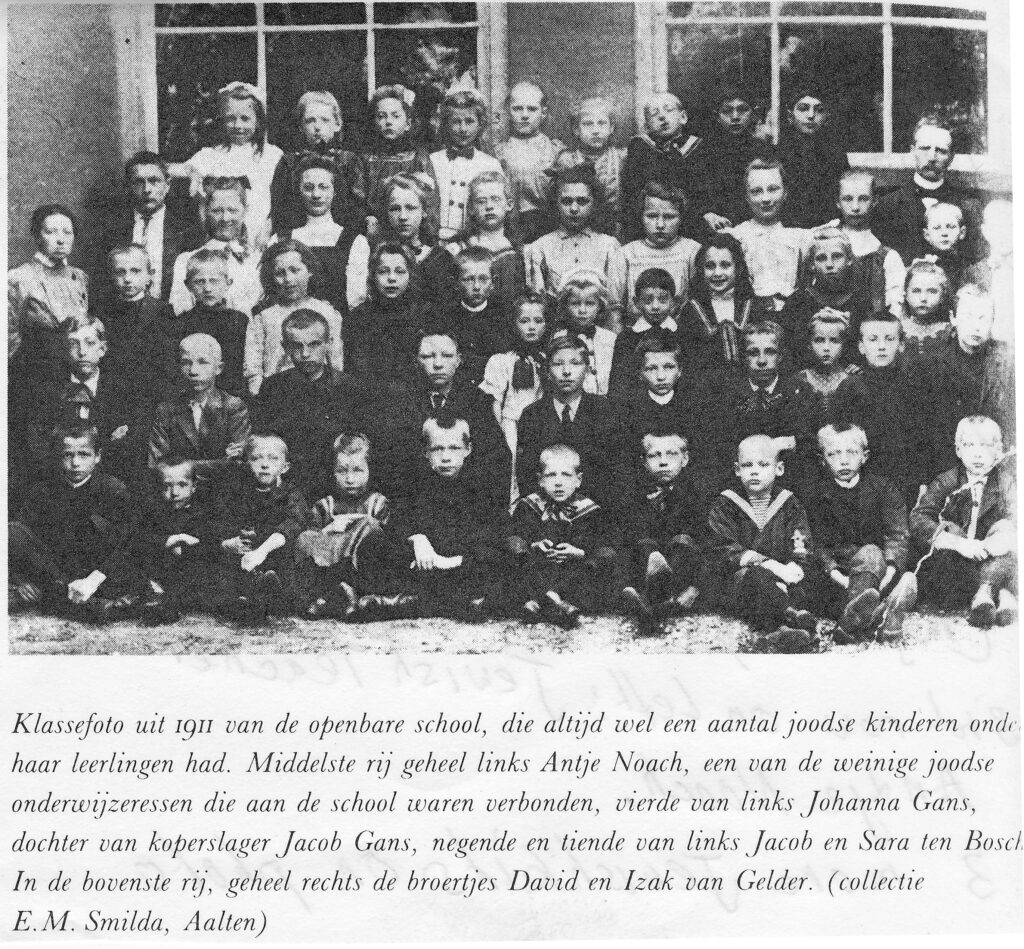

He recalls placards affixed everywhere with “Eternal Jew” images emblazoned on them. Soon, the yellow star of David became a symbolic marker that invited abuse. “We, as kids, were beaten up — quite severely at times. Grown-ups didn’t interfere. They were afraid. The police seldom intervened.” Schoolmates he counted as friends turned on him, yelling epithets. “I went to school with great trepidation. Things got worse and worse, until every aspect of my life was affected. You felt you were an unworthy person. That you didn’t have the right to walk the same streets as other people. It made me feel terrible and awful and angry.”

Schools were finally segregated, which he viewed as a welcome relief. “We were a pretty intelligent and rowdy bunch and we had a lot of fun in fact. We were all in the same boat. We were all together. That was the best part of it.”

By 1942, people started disappearing. “Nobody talked about it,” Lou said. “Not the teachers, not the parents. They didn’t know how to talk about it. They didn’t want to believe what was happening.” The fear turned personal when his girlfriend, Anita, was arrested along with her mother and sister. “I was very, very heartbroken for a long time because she was really my pal. We did homework together” He later learned she and her family died at Sobidor concentration camp.

As early as 1942 Jewish men were rounded up and taken away. It happened to Lou’s father, who ended up in the work camp, Ommen, where men worked clearing forests for agriculture, but in truth awaited transit to concentration camps and certain death. When the elder Leviticus learned of his group’s impending transport, he concealed himself in one of the deep trenches the men dug and escaped at night. Lou has since documented his father was the only prisoner from his work detail to escape alive. While in hiding, Max got word of his escape to Sera, who fled to a prearranged safe house in the country. Lou, in school at the time, was unaware of the unfolding intrigue. His first inkling of it came when an unfamiliar man came there one day with a note from his mother.

“My mother’s note said for me to go with him. The man told me, ‘Your mother’s waiting for you. Don’t worry.” Of course I was worried. I didn’t know what was happening. I had never seen him before, but I knew my mother’s handwriting, so I went. He took me into a hallway, took my coat off, gave me another coat without a star on it, grabbed my hand and we walked away. We went on a train. The train trip was frightening for me. We had to pass German police controls at various stations. By then I had been brainwashed so that I was sure I looked like any of those pictures of the Eternal Jew. I was afraid of anyone who had a uniform or boots or a dark coat on because those things represented Nazis. By then, I didn’t trust anyone any more. I’d lost my trust in the grown-up world.”

The pair passed through police checkpoints without a hitch. They got off at Amersfoort, a town 40 kilometers southeast of Amsterdam, where, it turned out the boy’s mysterious escort, a Mr. Van Der Kieft, was a plain clothes detective. Secretly, he was also a top operative in the Dutch underground movement that provided false identity papers, ration cards and safe havens to fugitives. As Lou soon found out, the underground network would be his lifeline. Van Der Kieft took him by bike to the farmhouse his mother had gone to. His father joined them days later. After two months in hiding, the family had to find refuge elsewhere when the farmer sheltering them demanded more money than they could pay.

Thanks again to the efforts of the underground, the family was put up at a house in Amersfoort belonging to a coachman, who lived on the ground floor. Lou’s family shared a pair of small rooms on the third floor. Between the two rooms were sliding doors. The back room opened on a veranda with a railing. The family had to remain quiet. They passed the time reading and playing board games. “I don’t remember that as being terrible because there was so much to read,” he said.

Then, one October afternoon in 1942, the bell rang and the word “police” was spoken at the bottom of the stairs. Raised voices barked, “Stay where you are. Don’t move.” Lou recalls his mother “started crying.” They knew the authorities had come for them. With police bounding up the stairs to the family’s third-floor hideaway, young Lou made a fateful split-second decision and, withouta word, clambered to the veranda opening, hopped atop the railing, and jumped. That moment of fear and flight was the last he saw his parents alive.

“Before I jumped the last thing I remember is seeing my dad close the doors behind me. That gave me enough time to get away. My dad didn’t hesitate. It happened so fast. Below me on the ground floor, luckily, was a large awning jutting out. I hit the awning, slid over it, landed on my feet and, whew, I was gone. I didn’t look back. I didn’t run either — a good thing, too, because police were out searching the grounds. I came to a house and climbed up on a rain pipe. I got to another porch, climbed over the railing there and found a big wash tub. I pulled the wash tub over me — it made a helluva racket — but nobody was home.”

He credits his quick actions to “pure self-preservation,” adding, “It was just pure instinct. I don’t know where it came from, except…I had seen other people being picked up by the police on the street and they never came back, and that wasn’t going to happen to me.” He does not second-guess his fleeing. “I knew I’d done the right thing because, number one, I’m alive. I’m sorry I couldn’t say goodbye and hug my mother and father. That is my only regret. That, and the fact they suffered and I couldn’t do anything.” His parents, like most of his family, were soon killed.

After eluding the police, he waited until dark, then fumbled his way to the home of a man who was active in the underground. When he arrived there the man’s frightened family explained the head of the house was in hiding. Lou felt safe for the moment but as he lay in bed that night he overheard the family discussing turning him over to authorities.

“When I heard that I decided that wasn’t going to happen. Early the next morning I stole some clothes and food, opened the door, and went on my own to the east.” Fending for himself in a world intent on his destruction, he learned to live by his wits’ end, foraging for food and shelter at local farms. But as a child on his own, he stood little chance for long. After days on the road, he came to the same farm he and his family began their hidden life at.

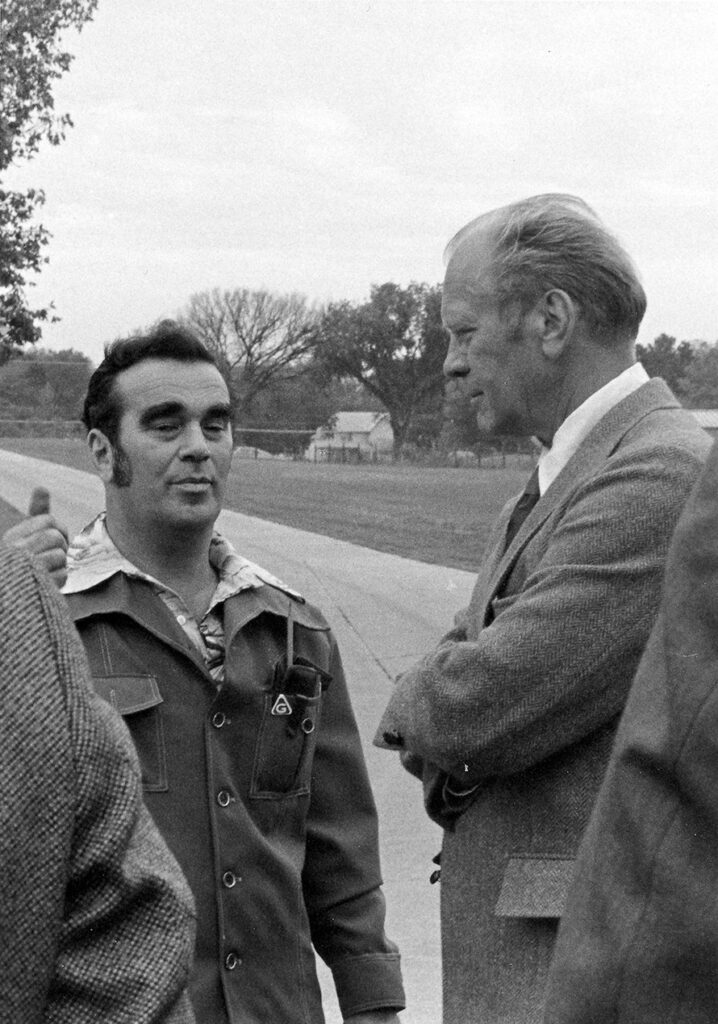

Fearing the farm was not a secure hideout, he was relieved when the underground placed him with Karel Brouwer, then a 24-year-old civil servant with a new wife and young child. Neither the first nor the last person Brouwer rescued, Lou stayed with him and his family for much of the remainder of the war.

“He’s a remarkable man. He took me to his home in Hamersveld. He practically adopted me. He never intended to be a hero, but somehow it was thrust upon him, and he risked everything to feed, shelter and keep me and others out of harm’s way.”

Lou still keeps in touch with his “second family.” In a fateful twist, the first refugees Brouwer helped were Lou’s aunt, uncle and maternal grandparents. Through his position in local government, Brouwer’s used the registration system to provide hunted Jews and non-Jews alike with false names and documents. Thus, Lou took on the identity of Rudi Van Der Roest, a Christian boy his own age from Amsterdam.

As Rudi, Lou lived the unencumbered life of a non-Jewish child. Whenever detained, his cover story was that he was away from home due to hardships caused by the war. The deception worked. “Each of us in hiding were stopped and interrogated by the Germans at least once or twice, so we knew how to lie with a straight face. You got very adept at that. Every time you did something to thwart the Nazis it made you feel good.” He enjoyed freedom but guarded what he said and did so as not to compromise his situation. “I had to be careful. I couldn’t afford any slips of the tongue, so I couldn’t get close to a lot of people. Whatever I wasn’t told, I didn’t ask. You learned that very quick.”

Life with the Brouwers was sweet. “A lot of beautiful things happened during the war,” he said. “There were times when I forgot the misery. I was extremely lucky to get through that experience, not unscathed exactly, but well-looked after.” He adds that not all hidden children were as lucky as himself. “The Brouwers loved me. They were good to me. In many cases, though, kids were shuttled from place to place and mistreated by their host families.”

As a base for the underground the Brouwer home witnessed many comings and goings. All the activity must have raised suspicions because, in February 1945, the police raided it. The whole family, including Lou, then 14, was home that day. The police found mounds of incriminating evidence. Everyone was interrogated on-site. Crying after being roughed up, Lou regained enough composure to hatch another escape. He explains: “I asked if I could use the toilet, and the police said I could if I left the door open. The toilet was situated behind a stairway, and when the bathroom door was opened it hid another door which led to a side room, which led outside. As soon as I entered the bathroom, I went through the side door and ran.”

He ran all the way to the city hall building, where he knew underground contacts operated. There, he found that Brouwer, who’d also escaped, had arranged for his transport to a new safe house — a farm belonging to Peel Van Den Hengel. It was there he worked and stayed until war’s end. When the Van Den Hengels insisted he be baptized Catholic, he complied. In April 1945, events unfolded at the farm that gave Lou a taste of Old Testament revenge. Blood was spilled, lives taken, eye-for-an-eye revenge extracted. It began when two German soldiers arrived to plunder the farm at gunpoint, ordering Lou and his fellow farmhands to load-up food and other supplies. Earlier, one of the soldiers molested a young maiden. Then they went too far, pushing Lou and another farmhand past the breaking point.

“I was digging holes with a very sharp spade, but I wasn’t working fast enough for one of the soldiers. He poked me in the kidneys with his gun, and that hurt. I turned around with that spade and I hit him straight in the throat and opened him up all the way. He sank to his knees. He didn’t utter anything. He bled to death on the spot. The other soldier came running, but didn’t see behind him one of the other boys, who struck him with a pitchfork. There was so much anger in us that we just went bezerk and cut them up into pieces. It’s something you wouldn’t do to a dog. I’m not very proud of it, but I’m not sorry about it. I wanted my revenge.”

After Germany’s unconditional surrender, he returned to the Brouwers. Then, much to his dismay, a humanitarian organization enforced a separation by placing him in a Jewish orphanage. “I hated it.” Always the escape artist, he hightailed it out of there and bummed around Europe with a jazz band. When a rift caused the group to split-up in Marseilles, he stayed on and later took to sea as a merchant seaman, applying his mechanical aptitude to ships’ engines.

After Germany’s unconditional surrender, he returned to the Brouwers. Then, much to his dismay, a humanitarian organization enforced a separation by placing him in a Jewish orphanage. “I hated it.” Always the escape artist, he hightailed it out of there and bummed around Europe with a jazz band. When a rift caused the group to split-up in Marseilles, he stayed on and later took to sea as a merchant seaman, applying his mechanical aptitude to ships’ engines.

In 1951 he made his way to Israel, not out of idealism, but rather the lure of a pretty blonde, whom he followed to a Haifa kibbutz. Finding communal life too restrictive, he left to study at the Israel Institute of Technology, where he earned an engineering degree.

After obtaining his Ph.D. in the states (at Purdue University) he returned to Israel. He served in two wars against Egypt — in 1957 and in 1973 (The October War). In the latter conflict he was a liaison between the U.S. and Israeli armies, working with the armored division and corps of engineers on the mobility of military vehicles and their off-road conditions. He helped engineer a bridge crossing the Suez Canal. He came to live in the states for good in 1974, joining the UNL faculty in 1975.

Although he downplays it, his wartime experience has haunted him. How could it not? All during the war, and even long after it, he did not know his parents’ fate. “I never was sure, really. I think I really didn’t want to know. I was always hoping they were still alive somewhere,” he said. Only much later did he confirm they were gassed to death at Auschwitz just a few months after their capture. He remains as unforgiving about what was done to his family as he is unrepentant about what he did to prevail. “I’m not very, shall we say, humanitarian in my beliefs. I still adhere to the principle that your best enemy is a dead enemy, which I know is not a very Judeo-Christian thought, but I don’t give a damn — that’s the only way I survived.”